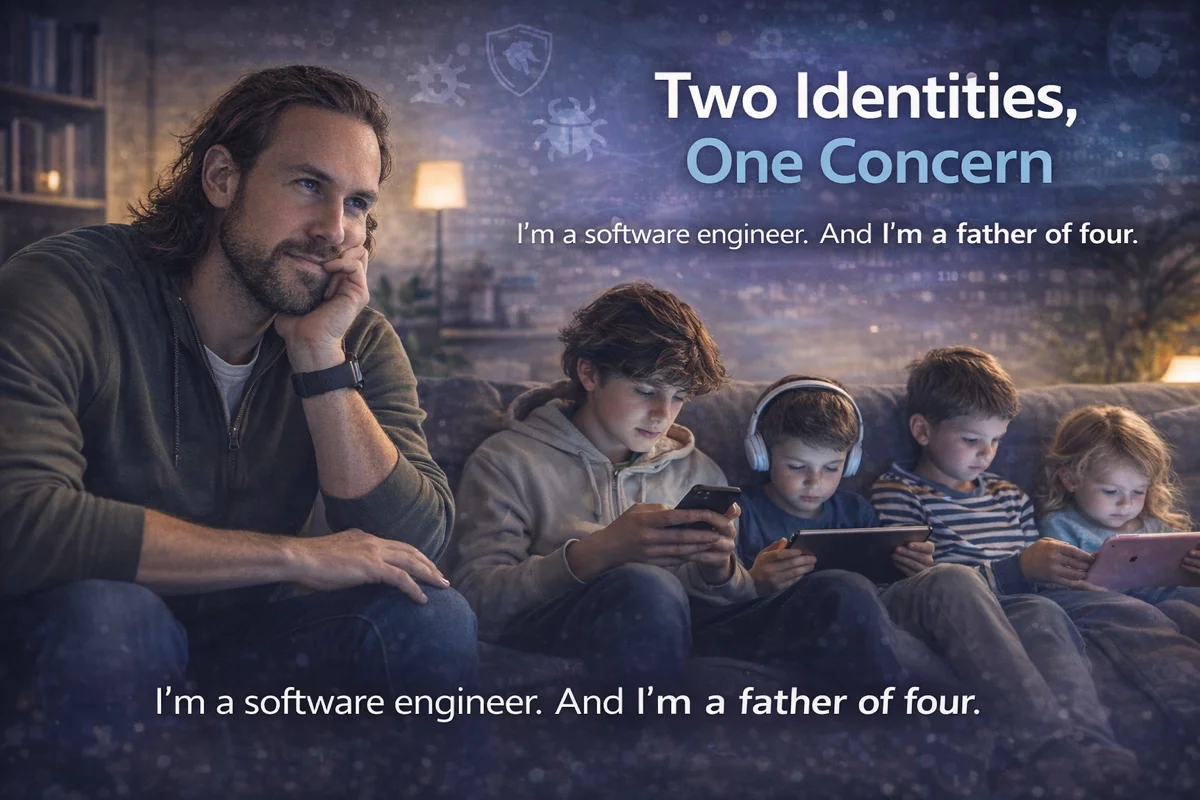

Two Identities, One Concern

I’m a software engineer. And I’m a father of four.

Professionally, I spend my days thinking about bugs, security vulnerabilities, and scalability challenges. I optimize systems, hunt down edge cases, and design architectures that can handle growth. It’s work I love—solving puzzles, building things that matter, making complex systems run smoothly.

But when I come home, there’s a different kind of complexity waiting. Four children, each with their own needs, their own personalities, their own relationship with the devices that surround us all. And lately, I find myself worrying about something that doesn’t have a clear solution or a neat architectural pattern.

I’m worried about the health of our children. Not just physical health—mental health too.

The Pattern I Can’t Ignore

We see it more and more in the news. More children struggling with obesity. More mental health issues among young people. More pressure, less rest. More screen time, less time outside. The statistics are sobering, and they’re trending in the wrong direction.

As an engineer, I’m trained to recognize patterns. And the pattern I see here is concerning: we’re optimizing everything in our children’s lives. Efficiency. Speed. Stimulation. More activities, more content, more connection. But at what cost?

Children are not systems you can scale endlessly without side effects. They need downtime. They need boredom. They need unstructured play and time in nature. They need sleep that isn’t interrupted by notifications. They need the space to simply be children.

I’ve watched my own kids reach for their tablets first thing in the morning. I’ve seen them get frustrated when screen time ends—not because they were having fun, but because they were caught in loops designed to maximize engagement. I’ve noticed the difference in their energy and mood after a day spent mostly outdoors versus a day spent mostly on screens.

The Engineering Perspective

Here’s what bothers me as someone who builds software: I understand how these systems work. I know about engagement metrics, feedback loops, and variable reward schedules. I understand that some of the brightest minds of our generation are working to capture and hold attention—including the attention of children.

It’s not evil. Most developers aren’t sitting around thinking about how to harm kids. But the incentive structures are misaligned. When success is measured in time-on-screen and daily active users, the product will optimize for those metrics. The side effects—the anxiety, the shortened attention spans, the difficulty with delayed gratification—are externalities that don’t show up in the dashboard.

As engineers, we talk about technical debt: shortcuts that make things easier now but harder later. I wonder if we’re accumulating a different kind of debt with our children. Are we trading their long-term wellbeing for short-term convenience?

The Parenting Perspective

As a parent, I see this up close every day. I know how hard it is to maintain balance. I know the relief of handing over a tablet during a difficult moment. I know the negotiations, the meltdowns when limits are enforced, the constant pressure to just give in.

I also know my own failures. The times I’ve scrolled my phone instead of being present. The moments when I’ve used screens as a babysitter because I was exhausted. The hypocrisy of telling my kids to put down their devices while I check my email for the twentieth time.

Last week, my youngest asked if he could play “just one more game” before dinner. When I said no, he told me it wasn’t fair—because I was on my laptop. He was right. Children don’t hear our lectures; they see our behavior. And what they see is adults who are just as hooked as they are.

Finding room for boredom, movement, and simply being a child has become surprisingly difficult. Our schedules are packed. Every moment feels optimized. Even play has become structured, supervised, measured. When was the last time your kids were truly, completely bored—with nothing to do and no one to organize their time?

This Is Not About Blame

I want to be clear: this is not about blaming parents. Not at all.

We are all doing our best in a world that keeps accelerating. The pressures are real. The challenges are genuine. Most parents I know are thoughtful, caring people who want what’s best for their children. They’re also exhausted, overwhelmed, and trying to navigate terrain that didn’t exist when they were growing up.

The schools expect more. The activities demand more. The career requires more. And somehow, in between all of that, we’re supposed to carefully curate our children’s digital lives while managing our own screen addiction? It’s a lot.

But maybe—just maybe—we need to pause more often. Make more conscious choices. Ask not only “can we do this?” but also “should we want this?” Just because something is possible doesn’t mean it’s beneficial.

A Call for Conversation

My call to action is simple: let’s start the conversation. Not lectures, not guilt trips, not one-size-fits-all prescriptions. Just honest conversations.

- At school: How are we teaching digital literacy? Are we giving children tools to understand and resist manipulation? Are we creating enough screen-free time?

- At work: What’s our responsibility as technologists? Are we building products we’d be comfortable having our own children use? Are we considering the youngest users when we design?

- At the dinner table: What’s our family’s relationship with technology? What boundaries make sense for us? How do we model healthy habits?

Talk about screen use—not just setting limits, but understanding what’s behind the pull. Talk about mental health—normalizing the conversation so kids know it’s okay to struggle and ask for help. Talk about the example we set—because our children are watching and learning from everything we do.

What Truly Matters

As a society, we measure and optimize everything. Productivity. Engagement. Growth. We have dashboards for every metric imaginable. But I sometimes wonder if we’re measuring the right things.

If we’re going to optimize something, let’s optimize for what truly matters: healthy children, now and in the future. Children who can focus, who can play, who can be bored without panicking. Children who know they’re loved not for their achievements but for who they are. Children who grow up to be balanced, resilient adults.

I don’t have all the answers. I’m figuring this out just like everyone else. But I know that the conversation needs to happen, and it needs to happen now—before the patterns become too entrenched to change.

I’m a software engineer. And I’m a father of four. And I believe we can build a better future for our children—if we’re willing to question the systems we’ve created and the choices we make every day.